After Monday morning’s Supreme Court decision reviewing the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2011 batch of Clean Air Act regulations clamping down on carbon emissions, you would have concluded that the agency, and President Obama’s global warming agenda, suffered a grievous defeat—if you read only the press releases issued by the battalions of industry groups, red-state politicians, conservative academics, and advocates who had asked the Court to strike the regulations down. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, for example, whose brief to the Court fumed that EPA’s initiative was “the most burdensome, costly, and far-reaching program ever adopted by a United States regulatory agency,” crowed, that “the Supreme Court ruled [the agency’s action] unconstitutional.” With just a tad less bombast, Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott claimed victory, insisting that the Court had “overturn[ed] the EPA’s Illegal Greenhouse Gas Permitting Scheme.”

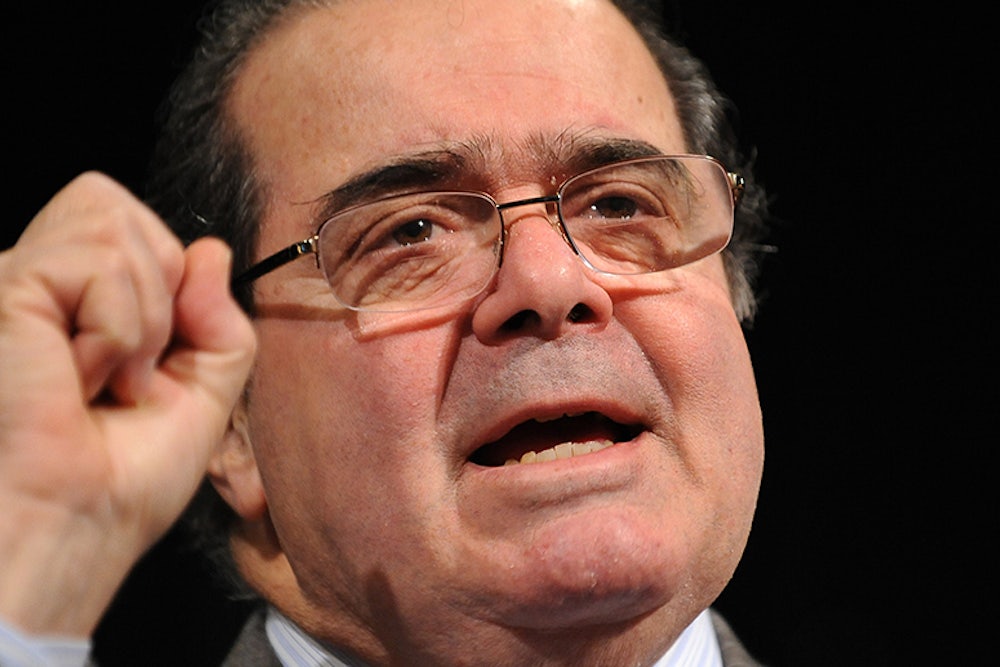

But things looked different to the Obama administration and supporters of President Obama’s anti-global warming agenda. The EPA called the decision “a win for our efforts to reduce carbon pollution.” Most—not all—mainstream reporters bought the administration’s version. Typical was the Wall Street Journal’s title for its account: “Supreme Court Ruling Backs Most EPA Emission Controls.” Justice Antonin Scalia helped the media reach that takeaway, by ad-libbing his own spin, as he read from the bench his opinion for the Court, “The EPA is getting almost everything it wants.” In effect, Scalia counseled his audience to look past the 5-4 majority (reflecting the Court’s familiar conservative-liberal blocs) that struck down the agency’s rule that, solely on the basis of CO2 emissions, anyone planning to construct or modify a “stationary source”—i.e., a structure of any sort—must include measures to “prevent significant deterioration” of air pollution levels and obtain a permit approving the plan. Instead, Scalia asked people to focus on the 7-2 majority ruling (with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy joining Scalia and the four progressive justices) that, though such “PSD” permits could only be required for sources of a narrow set of long-established pollutants, like sulphur dioxide and lead, once subject to the permitting requirement, facilities could be required, as the EPA had prescribed, to reduce CO2 emissions as well. That second point, Scalia underscored in his opinion, was “evidently regard[ed]” by Solicitor General Donald Verrilli “as more important” than the first; furthermore, the justice noted, leaving that second half of EPA’s rule in place would enable the agency to regulate sources that “account for roughly 83 percent of American stationary-source greenhouse-gas emissions,” compared with just 86 percent, had the first half been allowed to stand.

In denying the agency the authority it had claimed to reach that additional 3 percent, Scalia larded his opinion with pages of grandiloquent rightward spin, evidently designed to reassure the conservative faithful that he, and the two conservative colleagues who joined him, had not forsaken their duty to rein in the perennially “overreach”-prone feds. He repeatedly castigated the EPA for “tailoring legislation to bureaucratic policy goals by rewriting unambiguous statutory terms.” (Never mind that a unanimous D.C. Circuit panel, including the very conservative former Chief Judge David Sentelle, had found the agency’s interpretation “unambiguously” correct, as had Scalia’s four progressive colleagues.). “Were we to recognize the authority claimed by EPA,” Scalia sermonized, “we would deal a severe blow to the Constitution’s separation of powers.”

Not coincidentally, Scalia took from influential D.C. Circuit conservative Judge Brett Kavanaugh his recipe for straddling between his right-wing constituency’s strident anti-government orthodoxy and long-established rules of judicial deference to congressional and executive regulatory authority. Dissenting from the D.C. Circuit Court’s refusal to review Judge Sentelle’s approval of the EPA’s regulation en banc (i.e., review by all D.C. Circuit judges), Kavanaugh likewise pummeled the EPA for allegedly asserting a “kind of statutory re-writing authority [that] could significantly … alter the relative balance of powers in the administrative process.” Then he pivoted to an alternative interpretation that empowered the EPA to clamp down on CO2 emissions from all but 3 percent of the stationary sources it had originally sought to cover. Scalia gave Kavanaugh’s interpretive formula a slight tweak that caused even less disruption to existing EPA regulations, following a suggestion made at oral argument by Solicitor General Verrilli. By thus responding to a high-profile high-stakes Obama initiative, the Court’s solution bears a notable family resemblance to Chief Justice Roberts’s decision to uphold the Affordable Care Act individual mandate—ruling it beyond the bounds of Congress’ power to regulate commerce, while upholding it as an exercise of the tax power. That piece of high-wire strategic balancing was likewise derived from a D.C. Circuit opinion by Judge Kavanaugh (as I explained in this magazine).

Unlike Roberts’s solomonic resolution of the Obamacare mandate challenges, however, the Kavanaugh-Scalia slice-and-dice global warming decision has no apparent substantive basis, nor operational point; it provides zero guidance for EPA, or other agencies, as to how in the future they should craft regulations, to avoid getting slapped down for “rewriting” laws in the guise of interpreting them. Scalia’s opinion, after condemning the EPA for reading an implicit exception into one provision of the Act, managed to reach essentially the same regulatory result as the agency did, only by reading substantially the exact same exception into another provision of the law. Essentially, what the decision tells the Executive Branch is—if there’s any rewriting of statutes to be done around here, we’ll do it, or at least we’ll decide when you can do it.

It would seem tempting to dismiss the majority’s watch-what-I-say-not-what-I-do posturing as empty Washington turf-driven pique. Tempting but wrong. Although never noted in the opinions, this case actually represents an intensifying, if silent, dialogue, in which the Court and the Obama Administration are sorting out their respective roles filling governance gaps left by a dysfunctional Congress that can’t or won’t pass even necessary updates to important existing laws. As American University environmental law expert Amanda Leiter wrote earlier this year, the Clean Air Act “has aged, and its language and regulatory structures don’t comfortably fit the modern problem of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.” In Monday’s case, both the administration and the Court, or at least seven members of it, readily acknowledged that this law is the nation’s only instrument to handle this urgent national problem—and that, as written, it cannot be applied without producing “absurd,” indeed, catastrophic results. And both sides, however silently, took for granted that Congress will not act to make those or any other essential revisions. In effect, three of the five conservative justices recognized that inaction on climate change is not a sound option, and that implicit exceptions must be read into the literal text of the Clean Air Act to make action possible. They made clear that it is they who retain the power, ultimately to decide when to make those policy and political choices, and, to an undefined but significant extent, how to make them.